Front Page

Mercury News

September 4, 1989

CASTRO IMPORTS U.S. HOUSING IDEA

By KATHERINE ELLISON, Mercury News Mexico City Bureau

In a mango grove outside this capital city, Cuba is testing a radical notion imported from Berkeley.

The concept: low-cost housing that's also ecologically healthy -- and not ugly.

Just a few yards away from a contemporary Cuban standard issue -- a squat, pink block of flats, stuck on barren, razed land -- work is under way on a novel, custom-made community of apartments of exposed brick and concrete, winding gracefully through the mango trees.

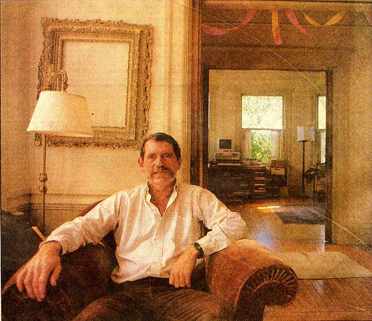

Architect Huck Rorick caught Fidel Castro's attention with inexpensive housing plan.

Called "Las Arboledas" -- The Groves -- the planned "micro-district" for 20,000 is the dream of Berkeley builder Huck Rorick, 48. Rorick struggled with Cuban bureaucrats for eight years before he caught the ear of Fidel Castro, who, he says, shared his vision that "cheap housing can also be wonderful."

Urban housing is a current Castro obsession. Though Havana lacks the homelessness that plagues most other big Latin American cities, it does have a severe housing shortage. In large part, the shortage is due to the government's previous preoccupation with developing rural areas, as well as bureaucratic delays in approving construction projects in Havana.

Up to 30,000 people in the capital live in homes declared "uninhabitable," with tens of thousands more crowded into much-too-close quarters. Divorced couples, for instance, are frequently forced to stay together for lack of anywhere else to go.

Severe new housing need

Each year, planners say, at least 100,000 new units are needed in this city of 2 million -- a need construction crews have not been able to fill, thus adding to the city's housing shortfall.

At the same time, officials acknowledge an increasing antipathy for the usual type of urban housing.

''Cubans have begun to reject buildings that all look the same," says architect Gina Rey Rodriguez, director of a new commission to redevelop Havana. "There have been cases where people have even lost their way trying to find their homes."

Rorick's project, says Jill Hamberg, a New York-based urban planner who has written extensively on Cuban housing, is one example of how officials are casting about for an answer -- namely, housing that is still cheap but more appealing than uniform blocks of apartments.

This rare case of American involvement in Cuba -- the countries broke formal relations in 1961 -- took shape when Castro and Rorick shook hands on their deal in March of last year. Four months later, construction began on Las Arboledas, which, like all Cuban housing, is wholly government-funded.

Besides being more aesthetically appealing than most of Cuba's modern urban housing, Las Arboledas is meant as a model for how neighborhoods can preserve the environment -- a value still novel in Cuba but dear to Rorick, who moved north from Los Angeles 30 years ago to escape the smog.

Planned for public transport

The planned community, located five miles south of Havana's center, is designed so residents can rely on public transportation. Its 5,000 dwellings will be placed around plazas, within walking distance of restaurants, markets and outdoor theaters.

In addition, each three- to five-story building is designed to save energy with natural ventilation, instead of the electric fans common in Cuba. To keep things even cooler, trees and grass will be preserved and pavement kept to a minimum. One of the most up-to-date ideas will be a sewage- and water- recycling system based on a series of lakes, instead of the usual mechanized plant.

To be sure, Las Arboledas wouldn't fit into most urban settings, since it's designed for bucolic surroundings. Yet its sensitivity to making life more comfortable and its techniques for saving energy while protecting the environment are prototypes, says Rey, "for what we need for the future."

Where Cuba had a need to innovate, Rorick yearned for an opportunity. A part-time architecture professor at the University of California, Berkeley and head of a small residential construction firm, he long ago grew impatient with what he feels are constraints on building homes in the United States.

''I want to build beautiful housing for regular people," he says. "But today, only five to ten percent of people in the U.S. can afford a new home. Architects are working only for the wealthiest people. In Cuba, it's the opposite."

Rorick also relished the idea of building an entire town based on innovations in energy use, sewage treatment and transport. After traveling to Cuba as a tourist in 1978, he felt he'd found the ideal setting.

A few months later, he was invited back by the Cuban government, along with a group of other U.S. architects and urban designers, several of whom continue occasionally to consult with the Cubans.

For Rorick, it was just the beginning of what would be dozens of other trips, and several years of planning -- and lobbying.

Exempt from sanction

The U.S. economic blockade of Cuba, in effect in various forms since 1960, prohibits most American citizens from spending money or doing business on the island. Rorick says his activities fall under an exemption for "educational exchanges," since each time he and his colleagues go, they share information with Cuban counterparts. In addition, the Cuban government pays all of Rorick's expenses and he receives no compensation for his work.

In the early 1980s, Rorick founded Groundwork Institute, a non-profit corporation concerned with low-cost housing and the Third World. Its supporters include Berkeley Mayor Gus Newport, Rep. Ron Dellums, D-Oakland, and Los Angeles film maker Haskell Wexler.

Working from home

From his office at home, Rorick made contact with experts on architecture and sewage treatment throughout the United States, and on each trip back to Cuba brought with him a new consultant or new literature.

Cuba offered Rorick two major advantages as a site for testing his low-cost housing concepts. The first, he says, was a government that, while cost-conscious, was committed to improving community life in ways overlooked in the United States.

Cuba's second advantage was a unique, cost-free labor force, called "microbrigades" -- small teams of basically unskilled workers, often bureaucrats freed temporarily from their regular jobs, but kept on salary to work on housing construction.

Plans for Las Arboledas were accepted by the early 1980s, but progress was slow.

''No one ever came and confronted me, but I felt there was opposition," says Rorick. He blames what he calls "the forces of cheapness" favoring the predominant pre-fab techniques.

Finally, in March of last year, he went straight to Castro. In a seven-page letter, Rorick told him that "Cuba's housing should be beautiful" and healthy, and that it could be both at a low cost, thus serving as an international inspiration. He then described Las Arboledas and its long history of delays.

Meeting Castro

Soon afterward, Rorick was introduced to Castro during a meeting with a group of U.S. urban consultants who'd been invited to exchange ideas about Havana.

''Rorick! Hmmm," Castro said, looking the builder in the eye as he shook hands down the line.

Later, Rorick says, Castro told him, "I read your letter. Carefully. . . . Now what about this project?"

Castro by then had already commented in his speeches on the need for more appealing housing. After Rorick again described the delays plaguing Las Arboledas, the Cuban leader told him: "If you are looking for an ally, you have one."

From then on, work on the new project moved much more swiftly.

Rey says the cost of the first 500 dwellings will be from $1,000 to $10,000 each, depending on the rate of exchange used, plus 15 percent more of the total to include city services such as lights and running water. The project's initial costs will be "a little more expensive" than for other contemporary housing, she adds, "but we think it's worth it."

Rorick responds that while he's spent more for quality in some areas, he's saved in others. For instance, he says, he's cut costs by avoiding traditional high-rise construction, which can be up to 200 percent more expensive. In the future, he says, Las Arboledas will continue to save money, in part because its innovative sewage system will cost less to maintain.

Rorick says the project will take a decade to complete, but the wait doesn't worry him. "I want it to take that long. I want its ideas to be able to evolve."

Section: Front

Edition: Morning Final

Page: 1A

Memo:See also related story on page 20A of this section.

Cuba - coping with isolation

Correction:SETTING THE RECORD STRAIGHT (publ. 9/5/89, pg. 2A)

Because of a reporter`s error, a story about housing in Cuba in Monday`s Mercury News referred to Gus Newport as mayor of Berkeley. He is a former mayor of Berkeley.

Illustration:Photos (2)

PHOTO: Michael Rondou -- Mercury News

Architect Huck Rorick caught Fidel Castro's attention with inexpensive housing plan

(color)

PHOTO: Katherine Ellison -- Mercury News

BUILDING THE FUTURE -- Cubans work on inexpensive homes planned for ecological health.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Copyright (c) 1989 San Jose Mercury News